There are places you visit, and there are places that visit you, lingering in your thoughts long after you’ve left. The Workhouse at Southwell is one of the latter. I’ve been three times now, and each visit leaves me humbled, thoughtful, and profoundly grateful for the life I lead.

As you walk up what is known as the “pauper’s path,” the same gravel track trodden by desperate souls for over a century, you feel the weight of history settle on your shoulders.

The first glimpse of the building is arresting. It’s a stark, symmetrical, three-storey block of red brick that looms over the Nottinghamshire landscape. It doesn’t look like a refuge; it looks like a prison.

This imposing structure, now meticulously cared for by the National Trust, is the most complete and best-preserved workhouse in England.

Built in 1824, a full decade before the infamous law that would spawn hundreds of copies, it was a prototype—a place of last resort that became the blueprint for a nationwide system designed to solve the “problem” of poverty.

As I stood there, before even stepping inside, I felt the same question form in my mind that has on every visit: was this a place of hope or despair?

A sanctuary from starvation or a sentence for the crime of being poor? It’s a question that echoes in every bare room and windswept yard within its walls, and one I was determined to explore.

The very path I walked is a deliberate part of the experience. It’s not just an entrance; it’s an induction. The National Trust, in its sensitive curation of this difficult site, ensures your journey begins not at a ticket desk, but by literally walking in the footsteps of the destitute.

This physical act collapses the centuries, forcing a moment of empathy before you even cross the threshold. It’s the first, powerful step in humanizing the stark history that awaits inside.

An Architecture of Division: Building a Social Theory

To understand The Workhouse, you have to understand the philosophy that raised its walls. This building was the brainchild of the Reverend John T. Becher, a local clergyman and social reformer whose ideas were so influential they became the celebrated model for the nationwide Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834.

This “New Poor Law,” as it was known, was a radical and brutal overhaul of how society dealt with its most vulnerable. It was built on two core principles that found their ultimate expression in Southwell’s design.

The first was the chillingly bureaucratic concept of “less eligibility.” This stated that conditions inside the workhouse had to be deliberately worse than those of the poorest, most overworked labourer outside its walls.

It was not meant to be a comfortable safety net, but a powerful deterrent. The second principle was the “workhouse test.”

To prove you were truly destitute, you had to be willing to submit to this harsh regime, surrendering your freedom and entering the institution. Outdoor relief—parishes supporting the poor in their own homes with food or money—was to be abolished.

Walking through the building today, you see how this ideology was translated directly into bricks and mortar.

The design, heavily influenced by prisons, is an exercise in control. The layout is cruciform, with wings radiating from a central hub.

This wasn’t an aesthetic choice; it was an engine of segregation. Upon entry, inmates were immediately classified and separated into one of at least four categories: able-bodied men, able-bodied women, the elderly and infirm (chillingly termed the “Blameless”), and children.

Husbands were sent to one yard, wives to another, and their children to a third. Families were systematically and brutally torn apart, with contact strictly forbidden.

From the windows of his central quarters, the Master could survey almost every corner of the exercise yards, a design rooted in the panopticon theory of surveillance.

It was a constant, unnerving reminder that you were always being watched. In a small but poignant act of defiance, you can still see where inmates scratched sundials into the brickwork of the few blind spots, reclaiming a tiny measure of their time and space.

This reveals the building’s true purpose. It was more than a shelter; it was a social laboratory. The architecture was the primary tool in a vast experiment to re-engineer the morality of the poor.

By controlling every aspect of the physical environment—who you saw, where you walked, when you worked—the system’s architects believed they could correct the perceived character flaws of “idleness and profligacy” that they saw as the root cause of poverty.

The Workhouse was a machine for reform, and its moving parts were the people trapped inside.

The Unforgiving Rhythm of Life Inside

Life for an inmate was a relentless, monotonous cycle, governed not by the sun or seasons, but by the tolling of a bell that dictated every moment from waking to sleeping.

The process of entering this world was one of systematic dehumanization. New arrivals were stripped of their own clothes—often their last connection to their former lives—forcibly bathed, and issued with a coarse, shapeless uniform. Personal identity was erased, replaced by the uniform of a pauper.

Then came the work. To “earn” their keep, inmates were subjected to hours of arduous, mind-numbing labour.

For men, this often meant pointless, punitive tasks. They would sit in the yards breaking stones into rubble for road building or crushing old animal bones for fertiliser.

One of the most notorious jobs was oakum picking: painstakingly unravelling old, tarred ropes by hand, a task that would leave fingers bloody and raw. The point of this labour was not always productivity but psychological warfare.

Some workhouses used cranks that inmates had to turn thousands of times a day, connected to nothing at all. The sheer futility was part of the punishment, a tool of deterrence designed to crush the spirit and ensure that anyone who could possibly survive outside would never choose this life.

For women, the work was a drudgery of domesticity on an industrial scale. They were responsible for the cooking, cleaning, and laundry for the entire institution, which could house up to 160 people. This meant back-breaking hours at the water pump in the yard and scrubbing stone floors on their hands and knees.

And for all this labour, the reward was a diet designed to be just enough to sustain life, but no more. It was bland, repetitive, and utterly joyless, a reality famously captured in Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist with the desperate plea, “Please sir, I want some more”.

The menu was dominated by bread and gruel, a thin, watery porridge. Meat was a rarity, served perhaps twice a week, and the “soup” was often just the water the meat had been boiled in.

To truly grasp the monotony, consider what a typical week’s diet looked like for an able-bodied man.

| Meal | Sunday | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday | |

| Breakfast | 8oz Bread, 1.5 pints Gruel | 8oz Bread, 1.5 pints Gruel | 8oz Bread, 1.5 pints Gruel | 8oz Bread, 1.5 pints Gruel | 8oz Bread, 1.5 pints Gruel | 8oz Bread, 1.5 pints Gruel | 8oz Bread, 1.5 pints Gruel | |

| Dinner | 5oz Meat, 12oz Potatoes/Vegetables | 1.5 pints Soup, 5oz Bread | 12oz Suet Pudding, 6oz Vegetables | 5oz Meat, 12oz Potatoes/Vegetables | 1.5 pints Soup, 5oz Bread | 5oz Meat, 12oz Potatoes/Vegetables | 8oz Bread, 2oz Cheese | |

| Supper | 6oz Bread, 1.5oz Cheese | 6oz Bread, 1.5oz Cheese | 6oz Bread, 1.5oz Cheese | 6oz Bread, 1.5oz Cheese | 6oz Bread, 1.5oz Cheese | 6oz Bread, 1.5oz Cheese | 6oz Bread, 1.5oz Cheese | |

| Based on typical Poor Law Union dietaries of the period |

Beyond Oliver Twist: Nuance, Contradiction, and the Seeds of Welfare

While the overwhelming impression of The Workhouse is one of hardship, the reality, as the National Trust’s exhibition reveals, was more complex. The grim stereotype, while largely true, contains surprising contradictions.

Stepping into the schoolroom, I was struck by this paradox. The regime was strict, a “no-nonsense approach” to education.

Yet, in an era when schooling was a luxury for the poor, the children of The Workhouse received a daily education.

They were taught to read, write, and do arithmetic, and older children were trained in trades that might give them a chance at a life outside the system.

For a pauper child, the education offered inside these walls was often better than anything they could have hoped for outside.

A similar contradiction can be found in the story of the Firbeck Infirmary, added to the site in 1871. Initially, medical care in workhouses was appalling, with sick inmates tended to by other, untrained paupers.

But the construction of separate infirmaries, influenced by the pioneering work of figures like Florence Nightingale, marked the very beginning of a state-run healthcare system.

The displays at Southwell trace this evolution, with rooms recreated to show its journey from a basic 19th-century sick ward to its final use as a residential care facility in the 1970s.

This leads to an uncomfortable truth. For all its horrors, for some people, The Workhouse was the better alternative.

The guaranteed, if bland, food, the rudimentary medical care, and the simple shelter it provided were preferable to starvation, disease, and exposure on the streets.

It was a place of last resort, but it was, for some, a resort that saved their lives.

Here lies the great irony of the workhouse system. It was born from a punitive, moralistic ideology designed to reduce state dependency and force the poor into self-reliance.

Yet, in its attempt to control and manage the destitute, it inadvertently created the foundational structures of the modern welfare state.

By gathering the poor, the sick, and the uneducated into centralized institutions, the state was forced to create systems to deal with them on a mass scale.

These workhouse schools and infirmaries, born of a desire to punish, became the first large-scale, state-administered systems for public education and healthcare.

They were the unintentional cradle of the very social safety nets—like universal education and the NHS—that would one day repudiate the workhouse’s cruel philosophy.

Echoes in the Halls: Experiencing The Workhouse Today

What makes a visit to The Workhouse so powerful today is the telling of the stories of the people who passed through its doors.

This is not a museum of dusty objects, but a place of human connection. Armed with a digital audio guide, I wandered through the largely bare rooms, the device triggering sounds and voices that filled the silence—the chatter of the laundry, the strict tones of the Matron, the quiet testimony of an inmate.

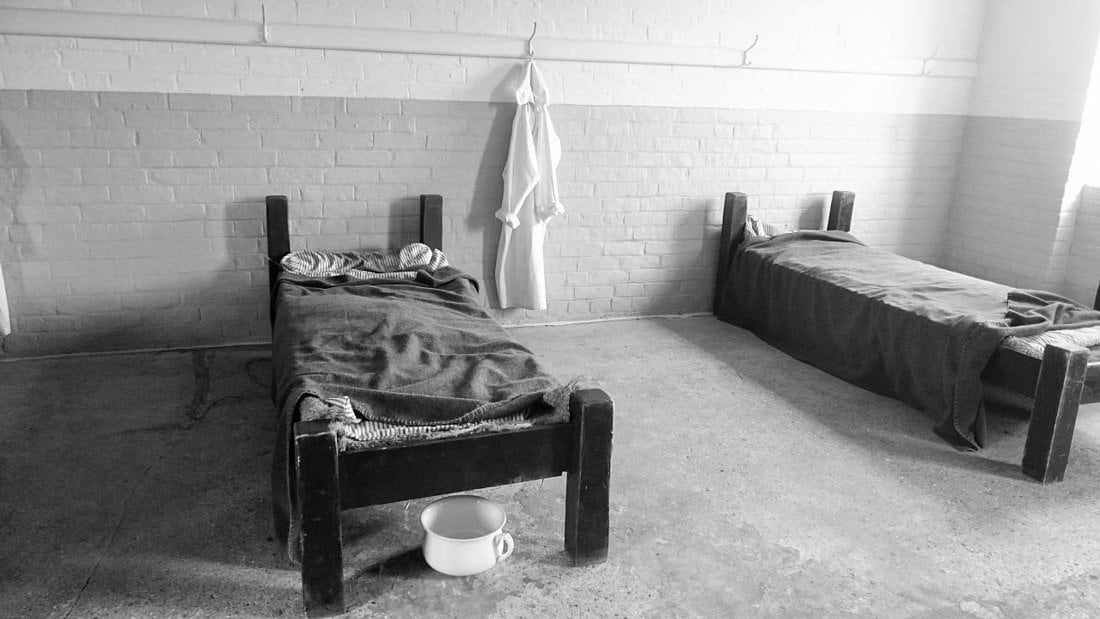

The tour takes you through the heart of the inmate experience. In the dormitories, with their simple iron-frame beds lined up in rows, you can almost feel the complete lack of privacy and the heartache of separated families.

You can stand in the punishment room, a dark, bare cell where rule-breakers were confined in solitude. And you can visit the “dead room,” a small, sobering outbuilding where the bodies of deceased paupers were kept before being taken for a pauper’s burial or, in some cases, sold to medical schools for dissection.

Yet, amidst the austerity, there is life. The recreated kitchen garden is a riot of colour and order, tended by volunteers and staff. Here, heritage vegetables and fruits are grown, with surplus produce sold to visitors from a barrow—just as it was in the 19th century to generate income for the institution.

The museum’s curatorial approach is masterful. With few original furnishings, it relies on the power of individual stories and small, personal objects to bridge the emotional gap of the centuries.

A single, worn child’s shoe, found during restoration, tells a more poignant story about a life lived here than any textbook could.

A birth and death register, discovered hidden in a ceiling, lists the names of real people, transforming them from anonymous “paupers” into individuals with stories. This focus on the specific and the personal is what makes the history feel so immediate and so deeply human.

The experience is brought even closer to home in the exhibits that detail the building’s later life, providing temporary accommodation for homeless mothers and children right up until the 1970s and 80s, a stark reminder that this history is well within living memory.

A Final Reflection: Leaving with a Heavy Heart and a Grateful Mind

Leaving The Workhouse and stepping back into the 21st century is always a jarring experience. The sounds of traffic return, the world is in full colour again, and the weight of the past begins to lift.

As on my previous visits, I left feeling humbled and deeply moved. The small frustrations of modern life seem utterly insignificant when measured against the daily struggle for survival and dignity that took place within those walls.

So, was it a place of hope or despair? I’ve come to believe it was both, and that is its most challenging legacy. It was a place of profound despair for those who lost their freedom, their identity, and their families. But it was also a place that offered the slimmest sliver of hope—the hope of a meal, a roof, and another day of life when all other options had vanished.

The visit forces you to reflect on how we, as a society, still grapple with the same issues today. The language of the Poor Law, with its neat categorisation of people into the “able-bodied” or “job seekers,” feels unnervingly familiar in contemporary debates about poverty and social welfare.

The Workhouse at Southwell is not just a relic of a bygone era. It is a mirror held up to our own time.

I cannot recommend a visit highly enough. It is not an easy day out, but it is an essential one. It is an unforgettable, eye-opening journey into our collective social history.

It’s estimated that one in six people in Britain have an ancestor who passed through the workhouse system. This isn’t just their history; it is, very likely, your history too.

Your Visit to The Workhouse: A Practical Guide & FAQ

Essential Information

- Location: The Workhouse and Infirmary, Upton Road, Southwell, Nottinghamshire, NG25 0PT.

- Opening Times & Prices: The Workhouse is open on select days, typically Wednesday to Sunday, but closes for a period over winter for conservation. It’s essential to check the official National Trust website for the most up-to-date opening times, ticket prices, and any special events before you travel.

- Getting There: The site is signed from the A612 on the outskirts of Southwell. There is a large, free car park located about 200 yards from the main entrance. Regular bus services run from nearby Newark, Nottingham, and Mansfield.

- Facilities: There is a café in the restored Infirmary building serving drinks, snacks, and light meals. Toilets, including accessible facilities, are available at the visitor reception, the café, and the main hub. There is also a second-hand bookshop on site.

- Accessibility: The grounds, ground floor of The Workhouse, and the Infirmary (which has a lift) are accessible. However, the upper floors of the main Workhouse building are only reachable by stairs. Mobility scooters are available to hire on a first-come, first-served basis.